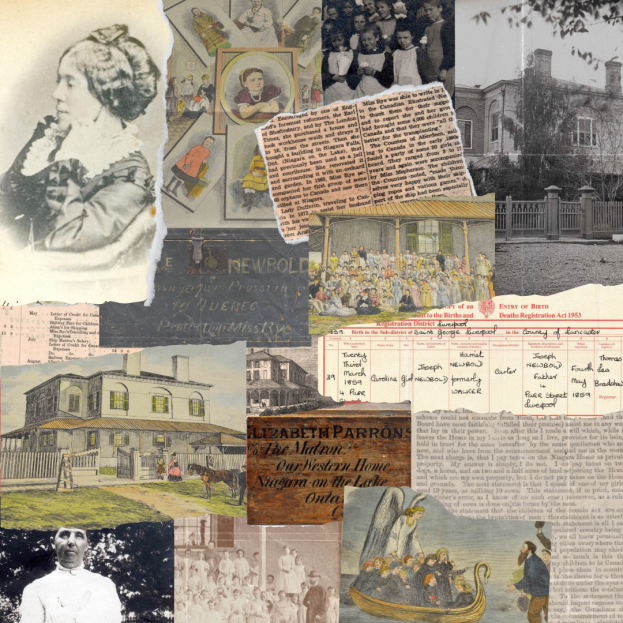

Marie Rye & Our Western Home

Maria Rye was an early suffragette from England, who is most known for her work with orphaned and destitute girls. Maria, being an advocate for emigration and social reform, founded the Female Middle Class Emigration Society (FMCES) in 1862. Through the FMCES, she transported young women and girls to British colonies like Australia and New Zealand. In 1867, after talking with the Canadian Government regarding the immigration of poor and destitute women and girls, she began focusing her sights on Canada. The following year, she brought several young women in their twenties to become domestics in Canada. Maria was growing increasingly aware of the issue of children and adolescent girls who had been deserted, destitute, and orphaned on the streets of England. By 1868, Rye started focusing her efforts on the emigration of young girls after purchasing and converting the former Courthouse and Jail in Niagara-on-the-Lake (NOTL) into “Our Western Home”. Later that year, she brought the first group of girls to Our Western Home. Maria spearheaded the first mass transportation of what became known as British Home Children to Canada and was later regarded by the Canadian Government as a leader in the Child Immigration field.

Previously Our Western Home had functioned as the town’s second courthouse and gaol (jail). The converted structure is said to have had the capacity to house 120 children, typically ranging from ages 5-16. When the children arrived from overseas, many had already undergone training for domestic and farm services. So, most children earned a placement within a matter of days, while the remaining children needed additional training. The home was self-sufficient with an orchard, a large vegetable patch, a small greenhouse, and a chicken coop, and the girls were expected to handle both domestic and garden duties (washing, sewing, cooking, growing vegetables, harvesting fruits, etc.).

The process for indenture was complex; the child and recipient household would be matched on a “best-case” basis. Meaning that most recipient households consisted of married couples or single women, who had been vetted by a reeve or minister. Children under 9 years old could expect to be adopted, those between 9 and 13 were typically fostered, and those 14 and up were indentured domestics until they reached 18. Placement households were expected to feed and clothe the children until they were 14, at which they were to be paid a fixed wage.

The program's “success” allowed Rye to acquire the Avenue House in Peckham, South London. Obtaining the Avenue House allowed Maria to help channel British Home Children (BHC) into Our Western Home. The success she had inspired others like Annie Macpherson to follow suit. But both Rye and Macpherson came under scrutiny in 1874 by Local Government Board Inspector, Andrew Doyle.

Doyle interviewed over 400 placed children and expressed concern regarding their welfare and aftercare. The report addressed discrepancies in the re-homing process, inadequate care or supervision, and a disregard, or complete lack of follow-up procedures. Through his research, Doyle discovered that most children had not had a follow-up visit for up to 2-3 years after placement, or they had essentially been “lost” or forgotten in the system. The younger children were frequently adopted into decent, affectionate homes, while the older children were placed into farm services where they consistently suffered through mistreatment, hardships, and deprivation.

Functioning without proper Government oversight and the lack-lustre record keeping or follow-up procedures, Doyle’s critique had repercussions that affected Our Western Home in the years that followed. The report proved to be so successful, that the Local Government Board halted the emigration of children from workhouses in 1875 and forced Maria to suspend her activities. About three years later, when emigration restarted, records became increasingly sparse. They included little more than the child’s initials and age, leaving documents without indication of a full legal name. Likewise, the person(s) who acted as a host family for the girls were sometimes recorded by age and initials, making it difficult to track progress or future whereabouts.

The management of Our Western Home was turned over to the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society. By the time of her retirement in 1895, Maria Rye had housed over four thousand children in OWH. The home would remain operative until the First World War, under the direction of Emily Bayley. Due to limited sources and record keeping, very little is known about the children who stayed at or were adopted/fostered. Today, uncovering the children’s names who went through Our Western Home is only possible by cross-referencing the Rye reports with a ship’s manifest information; however, this method does not always yield definitive or timely results. The strongest archival information is preserved in pamphlets and articles about Miss Rye’s work.

The property, which once housed OWH, is situated on Rye Street, nestled between two homes in Rye Park. While there is no surviving structure to commemorate the work of Miss Rye and the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society, the Niagara-on-the-Lake Museum is fortunate to have a number of artefacts and archival material which preserves the legacy of Our Western Home. Nevertheless, a plaque marks the site where the courthouse/orphanage once stood and details a brief overview of the location’s history.

The Museum's website contains a number of resources on British Home Children here: www.notlmuseum.ca/research/british-home-children