Alliances, Treaties, and Divided Loyalties

During the years prior to the American War of Independence (1775 – 1784), both the British and the First Nations were standing in the way of American expansion. The British because of their need to assert greater control over colonial affairs; and the First Nations, because they lived and thrived on land that white settlers believed held the promise of economic prosperity. To those settlers, they believed the First Nations were standing in the way of progress and of American “manifest destiny”.

Meanwhile, in the colony of Upper Canada, the relationship between First Nations people and the Crown was very much based on commercial and military needs. A vastly scattered system of trading posts relied heavily on the knowledge and cooperation of the First Nations.

But the result of the American War of Independence had a severe impact on the relationship between the Crown and First Nations people. Thousands of settlers loyal to the British crown, found safe haven in Niagara, swelling its population, and needing land. And at the same time the British attempted to compensate the First Nations for their losses during the war.

A series of treaties began with more than 30 treaties enacted dealing with land transfers and negotiations.

Under the 1764 Treaty of Niagara, the British acquired the rights to a four-mile strip along the Niagara River corridor from the Seneca Nation.

And later they acquired more land rights from the Mississauga for lands set aside by the Haldimand Proclamation of 1784, for six miles on either side of the Grand River as well as more land from the Anishinabek, a mere twenty kilometers downstream from the mighty Niagara Falls.

Trust and loyalty were the fundamental anchors of these treaties and land deals. How great a tragedy, therefore, that those qualities would in time become damaged and flawed. British loyalty would become lost in commercial interests. Society ideals and missionary fervour would divide and conquer previously hard-won loyalties.

In 1756 the British appointed Sir William Johnson as Superintendent of the British Indian Department. It was a position of great influence and power.

Johnson was, in all things, the consummate diplomat. And he cleverly protected British interests during the Anglo-French conflicts for dominance of colonial America.

But it was his collaboration with Indigenous communities that were so instrumental to the British victory over the French. He understood the value of Indigenous alliances. He learned to speak their languages.

And he gained their trust.

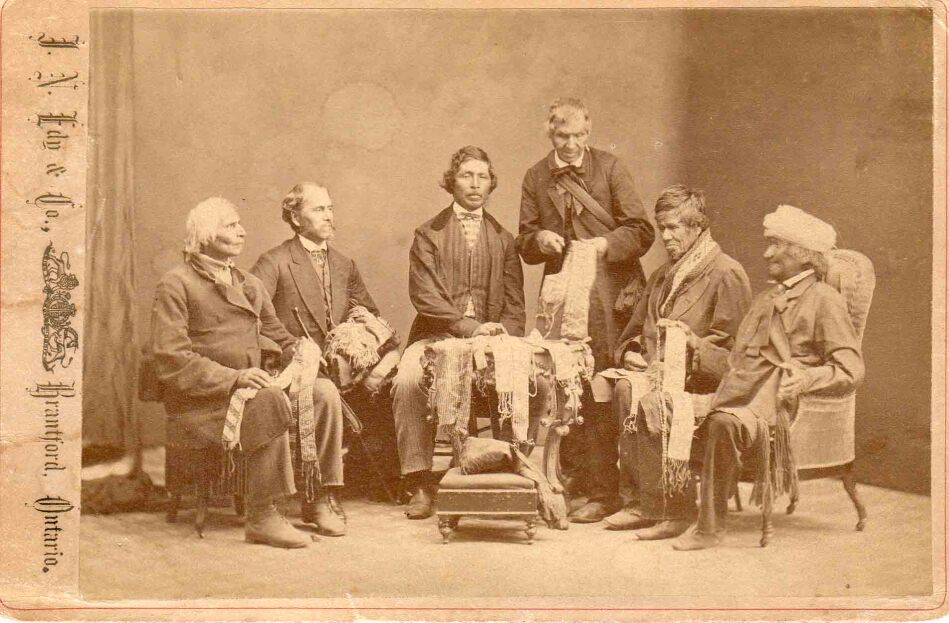

It was William Johnson who understood the significance of the Covenant Chain of Friendship, and oversaw the acceptance of the 1764 Treaty of Niagara. This historic wampum belt treaty renewed relationships, and reaffirmed pledges made by the British. Twenty four Indigenous nations participated in the agreement, including the Haudensaunee, the Anishinabek, the Algonquin, and the Huron.

Johnson also nurtured the young Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant.

And he married Brant’s older sister, Molly – who would be as powerful and legendary as her warrior brother. Joseph Brant spoke eloquently in support of Johnson at Confederacy Councils. And this gave Johnson his most valuable weapon - loyalty. It laid the groundwork that would benefit the British for decades, and in particular during the War of 1812.

However, policies introduced between 1868 and 1876 would result in Canada introducing The Indian Act, and with that Canada entered into more than a century of control and influence over nearly all aspects of Indigenous life.

For Indigenous people in Canada, trust and loyalty has indeed been a divided history.

Image: Six Nations Chiefs explaining wampum, Brantford, 1871.